How do we use technology to make better decisions? Gain insights? Craft and execute strategies? Why does it matter? These questions are top of mind as I wrap up a class of 154 individuals learning the principles of outside-in supply chain planning processes.

The continuation of the belief in the definition of today’s supply chain planning is a tangled web that we weave that is a bit of a mess.

An Answer I Got Wrong

Let me start with a story. The year was 2004. My client, named Pete, worked for Kraft (now Mondelez). I worked for AMR Research (now Gartner). This was before the split of Kraft into Mondelēz and Heinz, at the beginning of the implementation of Kraft’s global supply chain strategy. (He is now retired, and I should be.)

On the call, Pete gave me a hard time. His position was that the research that I was writing was not being aggressive enough in the definition of global supply chain planning requirements. I struggled to understand his point, and I am not sure that he was even clear in his own mind, but I remember the conversation.

As a high school debater, I love a good argument. (Old habits die hard.) I was working on a report on the Multi-Enterprise Inventory Management (often termed MEIO) and I challenged Pete. Was it that Kraft was not clear in its definition of supply chain excellence (which was true) or not clear on how to best use the system (which was also true)? Was it a system issue or a process definition problem? I could never get a clear answer from Pete. I don’t think that he was clear in his mind on framing the problem, but he was just sure that planning was not as effective. I brushed it off. I should not have.

At the time, the supply chain teams at Companies like Kraft were more mature in their understanding of supply chain planning than I find today. When I walk into a room at most Fortune 500 manufacturers, I am amazed at the loss of collective understanding of the principles of supply chain planning. Most are caught up in the hype cycles of pretty PowerPoints, sexy acronyms and vendor speak.

As for MEIO, I was excited to see some innovation in the space, but the creativity was short-lived. The most innovative of the technologies were quickly acquired, and the promise waned. If we are honest, we all now know that MEIO was an enigma. The reason? The software never expanded in scope to manage multi-tier inventories. Instead, it was a collection of deeper engines to improve safety stock calculations for the enterprise. The basic taxonomy of supply chain planning–the framework for a series of optimization engines– has not changed. What has changed are brief innovation periods to create better engines. Companies love engines with a series of over-hyped project implementations. The problem is simple. The industry is getting less value of supply chain planning than in the 1990s when the platforms were first defined, and supply chains were regional.

Too few companies stop to answer the questions:

- Is the solution giving a good plan? Is the plan feasible? How did the company perform to the plan?

- Are companies making better decisions through the use of the technology?

- How should they make a decision? What is the role of local management, divisional teams, and corporate organizations? Are they aligned?

- What defines supply chain excellence? How can new forms of technologies drive better insights?

- How do they decrease the time to sense and then respond?

Reflection

I recently taught a recent class on outside-in processes, I thought about Pete’s comments and the lack of supply chain planning process adaption to today’s reality. Suddenly, it clicked. I was clear. Pete was right. The solutions never morphed with the change from regional to global supply chains. I reflected on my experience as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison Overtime with Supply Chain Planning Implementations

| % of Inventory as Safety Stock | Forecastablity | Leadtime | |

| My Experience with Rolling Out Supply Chain Planning in the 1990s | 50-55% | 85-90% of items were forecastable with a COV less than .3 | Low Variability |

| Current State | 15-20% | 40-50% of items with COV greater than .7 | High Variability |

The traditional focus is on reducing error assuming that items at a location level (SKU) are forecastable. In the class, 92% of students had products with a Coefficient of Variability greater than .7. This level of variability is not forecastable at an item level, but yet their companies were trying to forecast using item-level forecasting based on shipment/order data inputs using a ship-from model. No company, in the class, measured market potential or baseline demand, and demand shaping/revenue management operated in a separate model from demand planning. One student shared that within his organization that there were over 1700 individuals with the term “data” in their title, but that the organization is longing for “insights.”

Observations

I think that we need to question the basics of today’s supply chain planning implementations.

- Measurement. In the class, 8 out of ten deployments of demand planning had a negative Forecast Value Added (FVA) measurement. Only three out of 72 companies were measuring FVA before the class. For most the measurement of FVA was a new concept. No company knew if they had a good plan. Why would we spend millions to implement a system with hundreds of planners that decreases the effectiveness of a process and increases the latency to make a decision? I know. It defies logic. The root issue is a lack of clarity on the definition of supply chain excellence, and supply chain governance. (Who should make what decision and what does good look like?)

- Inventory. Advanced planning models, often termed end-to-end planning, focuses on optimizing safety stock. In the evolution of the global supply chain, cycle stock and in-transit inventories grew faster than safety stock, as a result, in most global supply chains, the optimizers are only optimizing 15-20% of the inventory. The answer? Use network design technologies to optimize the form and function of inventory and right-size buffers.

- Model Adaptability. Only one company had backcasted to test the data model and the forecast engine. All blindly deployed item-based models without testing the validity of the demand planning models. (Global supply chains have five-to-seven flows each needing testing and model alignment.) Most of the discussion today, is on engines, not on models or testing. Most don’t know the difference. (Best pick methodologies select optimizers and do little for model definition.) The answer? Think holistically. In Table 2, I share a simple framework to spark your thinking.

Table 2. Demand Planning Basics

| Model Types | Engine Options | Demand Shaping | Locations | Data |

| Attach-rate Forecasting | Bayesian | Price Management | Ship To | Orders |

| Attribute-based Forecasting | Fourier | New Product Launch | Shop From | Shipments |

| Profile Planning | Lewandowski | Promotions | Channel Data | |

| Item-based Planning | Holt-Winters | Advertising | Weather | |

| Product-family Forecasting | Poisson | Product Positioning | Market Drivers | |

| Causal Factor Forecasting | Moving Average | Demand Drivers | ||

| Probabilistic | Exponential Smoothing | Event Data | ||

| Seasonal | Narrow AI | Economic Factors | ||

| Generative AI | Government Subsidies |

The impact is fivefold:

- Rise in Cost and Decrease in Planning Effectiveness. Over the past five years, supply chain planning headcount grew to hundreds, even thousands, of planners. One company increased the number of planners from 400 to 1300 post COVID. I know. Again, defies logic. We are rewarding reactive behavior.

- Decrease in Order Reliability. No company adjusted supply chain planning engines based on lead time variation. As lead times shifted and became more variable, optimization engines ran based on the assumption of initial values, companies did not adapt.

- Environmental Impact. 72% of the impact the environmental supply chain impact is outside of the enterprise; yet there is no easy solution to drive interoperability between networks. (Each network is a self-serving entity. As a result, there is no interoperability between Ariba and E2Open, or Elemica and GT Nexus/Infor. Today’s planned investment in network capabilities is low. (Less than 3% of respondents have this as a focus area in digital transformation efforts.)

- Increase in Bullwhip. The supply chain is a complex non-linear system. The Bullwhip game, invented in 1980, demonstrates the impact of the bullwhip effect on the supply chain. ERP and APS amplify the bullwhip impact, yet no planning technology reports the bullwhip impact and uses it as a planning parameter.

- Rise in Inventories. Across industries, we carry 28 more days of inventory. Yet, only 15-20% of the inventory is managed as safety stock. Few companies measure and manage in-transit inventories or cycle inventory decisions. And, while companies have purchased Multi-Enterprise Inventory Optimization technologies. They are deployed with the focus of enterprise safety stock management which is less-and-less effective.

Would you ever want to be a part of a project that increases cost, decreases working capital, and reduces order reliability? I think not, but this is the sad reality of implementing traditional planning taxonomies for a global supply chain. The sad reality is most companies want to implement this faster. Even contemplating adding generative AI. Laughing yet?

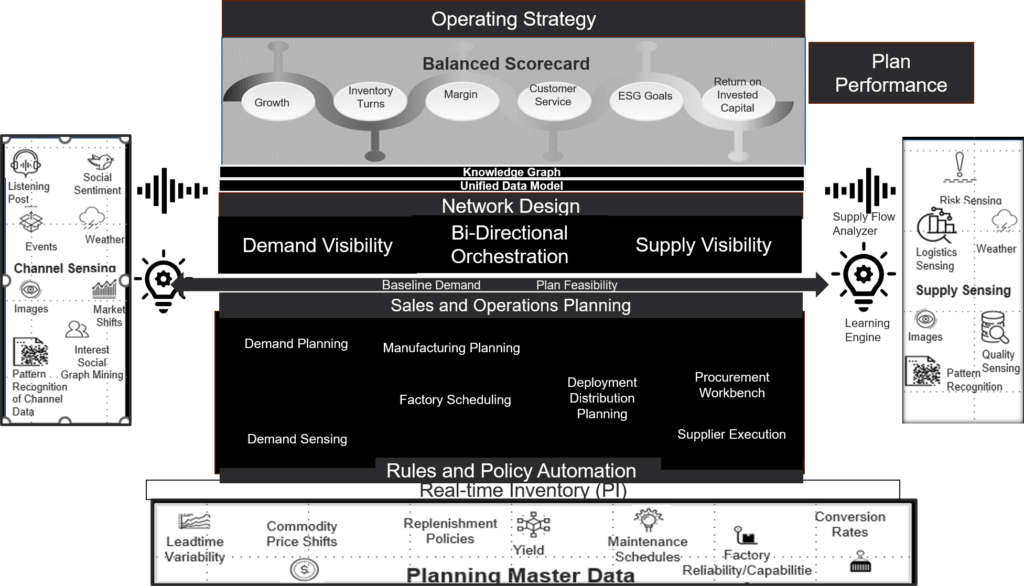

Searching For an Answer

Today, there is no clear answer, but in my class, I challenged the technologists (sixty-four of them) on how the use of graph, cognitive computing ontologies, NoSQL, machine learning, and narrow AI to improve planning. We explored the potential of a new model like the one depicted in Figure 1. While no one has the answer, what is clear to me is that today’s collective wisdom on “end-to-end” planning processes (which are anything but end-to-end) is not sufficient.

I continue to be amazed that the industry is alive with the hype cycle of generative AI but is moving so slowly to adopt the Web2.0 innovations and challenge conventional thinking.

Summary

I hope that this blog helps your thinking. What do you think? Where we go next?

I am placing all five of the classes on outside-in planning into a series on Youtube. The first class is live. The rest will be complete by the end of the week. I will teach another class in January, and will continue to host monthly calls with those that have completed the class and are continuing the testing.

I don’t know the answer, but I know what we have today is not driving the answer we need. Hopefully, by building a guiding coalition, we can drive new thinking to drive better outcomes. I owe this to Pete.