In 2002, I had the opportunity to work with General Mills. I walked away thinking, “What a great company!” At that time, the sales organization used more point-of-sale data than their competitors, they had an impressive and innovative IT team, and their supply chain processes were what I considered best-in-class. Over time, as I watched, this changed. The organization became more functional and political. They never leveraged their point-of-sale data to detect market shifts, and the supply chain organization prioritized cost reduction.

The organization failed to anticipate the downturn in the cereal market during the 2007 recession, and they lost consumer confidence in the organic product segment. This week, the organization reported that net sales decreased 2 percent to $19.5 billion from the prior year, and that their organic net sales were also down 2 percent. Operating profit of $3.3 billion was also down 4 percent. Diluted earnings per share (EPS) of $4.10 were down 5 percent; adjusted diluted EPS of $4.21 were down 7 percent in constant currency. My thought: depressing. And, this company was celebrated as #17 on the Gartner Top 25? I hung my head.

Organizations struggle to regain their footing during periods of market downturn. The essence of General Mill’s problem is that consumers are turning away from processed food. They are not able to successfully navigate the market downturn and give reliable guidance to shareholders.

The CEO’s response? “On our first priority of accelerating organic growth, our full-year sales trends did not meet our expectations, driven in part by continued value-seeking orientation and weaker consumer sentiment. On our second priority, we delivered another strong year of industry-leading productivity, with holistic margin management cost savings of 5% of the cost of goods sold. We exceeded our free cash-flow conversion target in fiscal ’25, achieving a 97% conversion rate. And we continued to deploy that cash in shareholder-friendly ways, including making further progress on reshaping our portfolio.” My thought: ouch! The CEO is a traditional thinker. The use of the supply chain as a functional organization within the organization to reduce costs.

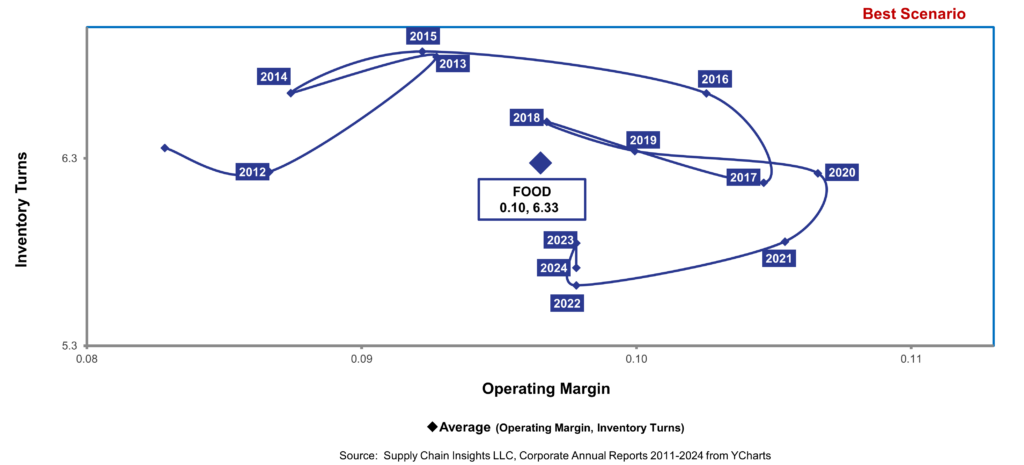

As shown in Figure 1, the CEO is facing a downturn in market potential for both margin and inventory turns. It is a tough slog. Packaged food consumption increased at the start of the pandemic, but the potential of the packaged food industry declined over the period of 2020-2024. With the rise in product complexity, inventory turns declined.

Figure 1. Food Industry Orbit Chart Sector Averages

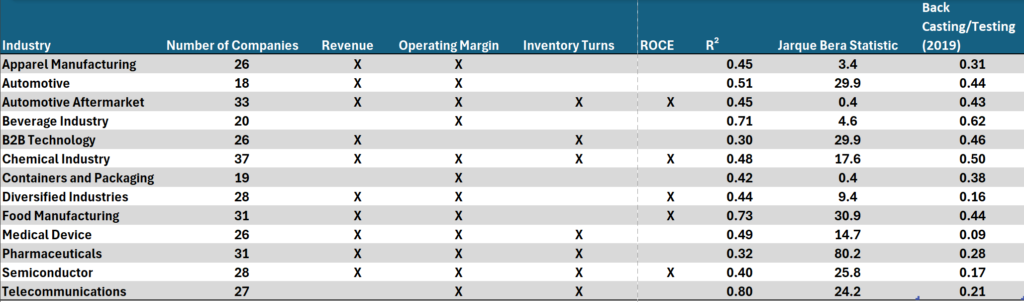

My knee jerk reaction was to send Table 1 to the CEO. Why would I do this? Based on the modeling completed with help from the IYSE group at Georgia Tech, we find a focus on operating margin, revenue/employee and ROCE can drive 73% of market capitalization/employee, while a focus on cost of goods reduces value. Over the last two decades, General Mills has become more functional and more focused on cost.

Table 1: Aligning the Organization to a Balanced Scorecard to Maximize Market Potential

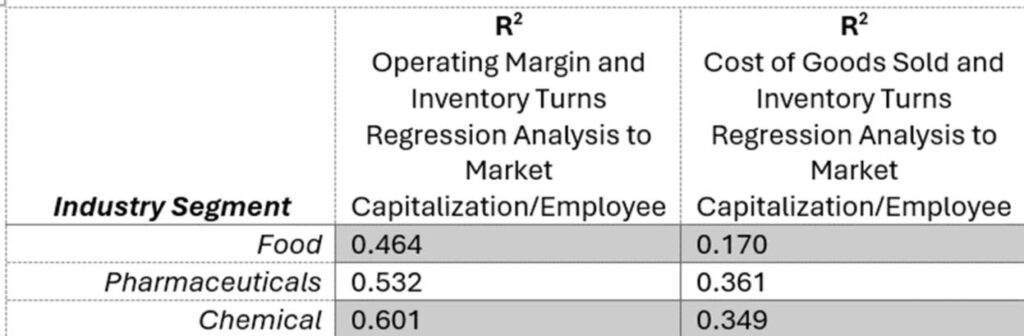

When we isolate the impact and only focus on only operating margin/inventory turns compared to a focus on cost of goods/inventory turns (as shown in Table 2), the impact is a 63% reduction in market capitalization/employee.

Table 2: Impact of a Focus on Cost of Goods Versus Operating Margin

This is a classic case of a marketing-driven supply chain that needs to be a market-driven value network. The downward slide on market potential is present in over 70% of the industry sectors.

Let me explain more on the concepts of becoming market-driven in the words of my students finishing my class this week..

Reflection

The outside-in planning class is a seven-class series designed to help companies understand the value of rethinking planning: the transition from inside-out thinking to being outside-in. This is my 14th class over three years. I have taught more than three hundred students. My goal is to build a guiding coalition to improve value. The class is available at no charge to manufacturers, but I no longer include technologists and consultants. The reason? Their paradigms are more dug in–tougher to drive change in their thinking–they think they know the answer. The second reason is that they do not have access to data. I find it is only when the student models the supply chain with the use of their data that their wheels start to turn.

Most of the students enter the class from traditional functional organizations and after learning the concepts struggle to influence the organization to think more holistically. At the end of the class, they speak a different language. My goal is to see fewer implosions like General Mills.

The class is not for the faint of heart. Each of the seven modules has homework and required reading. Ultimately, each student prepares a go-forward plan outlining how to apply the concepts within their organization. Here I share snippets of their plans.

Unlearnings

In the class, I ask each student to keep an “Unlearning Journal” to record their unlearnings. What is unlearning?

I firmly believe that unlearning must precede change management. (For a great understanding of outside-in processes, watch the video riding a backwards bike.) I think that the CEO of General Mills needs an unlearning journal.

In the class, following the viewing of the backwards bike video, we discuss how knowledge is not the same as understanding. Companies have traditional processes, but they have never questioned their knowledge of how to utilize market data to improve outcomes market-to-market. As a result, 80% of the data surrounding the supply chain is never used. This data is disparate: unstructured, image-based, and streaming. It does not easily fit into traditional supply chain models.

Traditionally, companies focus on the use of enterprise data — orders and shipments, which usually has a two- to four-week demand latency (the time from channel purchase to order receipt) and a 2-to 3-month market latency (the time from the market trigger to the translation into an order). This latency puts the organization at a disadvantage, making it reactive to a late signal.

Unlearning traditional thinking must precede organizational change management. Here are some entries from the class in their journals:

- Outside-in planning is a business model to align the organization on demand and supply risks and opportunities: it is not supply chain as we know it.

- The building of outside-in processes is not an evolution; instead, it is a new way of thinking.

- With schema-on-read technology approaches, we no longer have to focus on making data perfect.

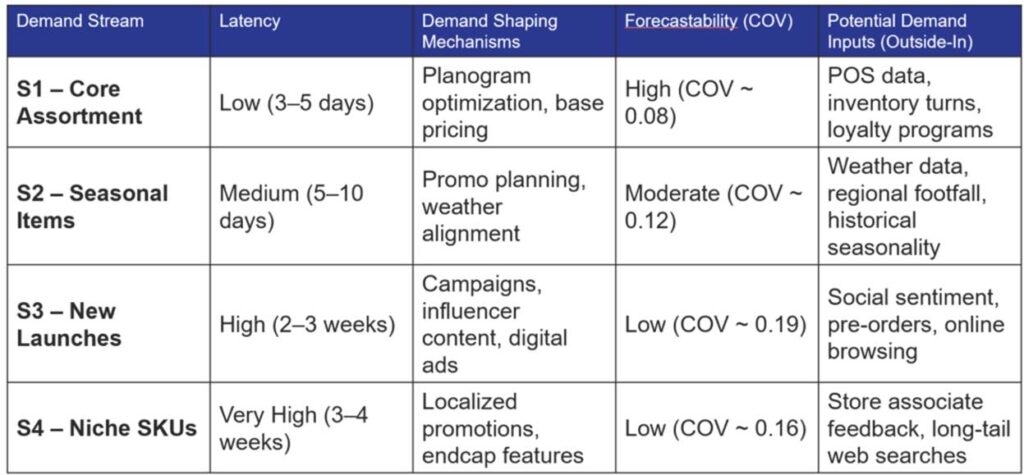

- One size planning does not fit all our needs. Companies need to recognize the differences in the rythmns and cycles of demand and supply streams.

What Is Outside-in Planning?

To embrace the opportunity, we must learn from history to unlearn. Here I share the definitions given by the students in their final homework submitted at the end of class:

“Outside-in planning is a proactive, market-driven approach that uses external signals (e.g., POS, weather, sentiment, competitor activity) to inform demand and supply decisions. Unlike traditional models, it is adaptive, signal-led, and focused on aligning decisions across planning, commercial, and operational organizational layers.”

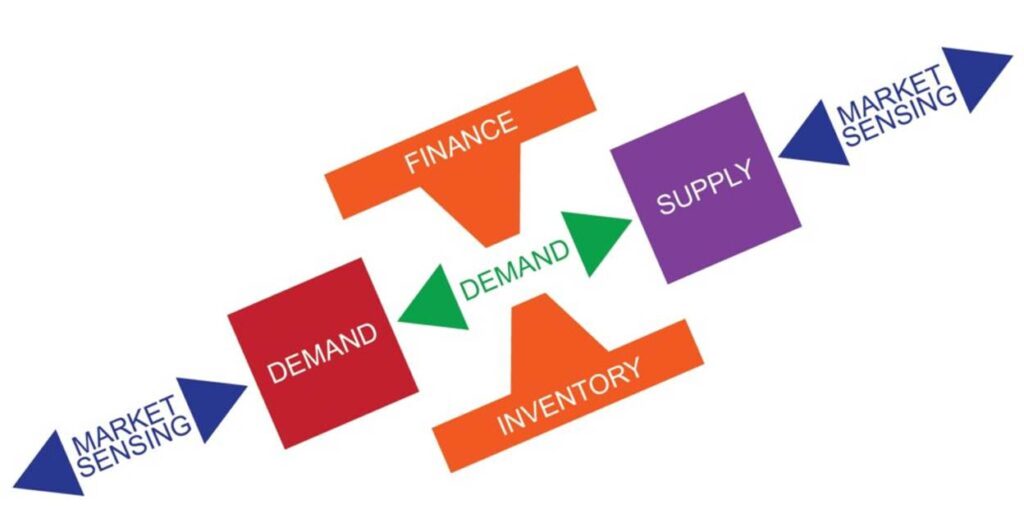

“Outside-in planning is a business value-driven approach vs a functional excellence approach. The typical supply chain focuses on cost, which does not translate to value. Conventional planning models use time-phased data, while outside-in processes sense and manage supply chain flows. The change from inside-out to outside-in allows a better understanding of demand flows and a recognition that there is more than one flow and different levers to pull in a bi-directional orchestration to manage the trade-offs.”

“Outside-in planning is a strategic shift in how we approach supply chain decision-making to drive business value. Rather than inside-out planning — based on historical orders, shipments, and internal capabilities and/or targets — it starts at one end of the network, with real demand signals from customers, channels, and even downstream partners, while considering supply network signals, and the ability to orchestrate dynamically and bi-directionally demand and supply.“

Navigating the River of Demand and Driving Outside-in Planning

One of the activities is constructing and analyzing demand flows. In the class, we define bi-directional orchestration opportunities from market-to-market to align demand and supply cycles and absorb variability.

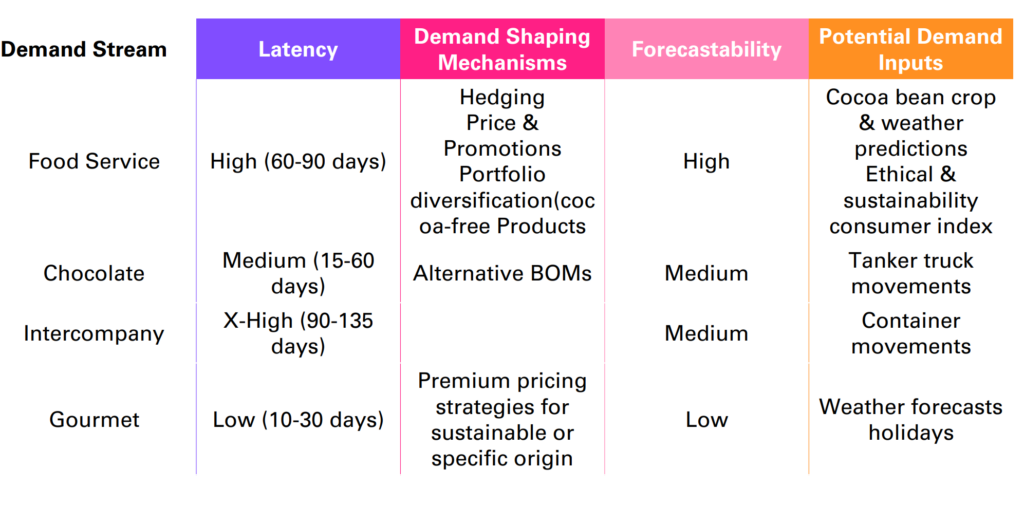

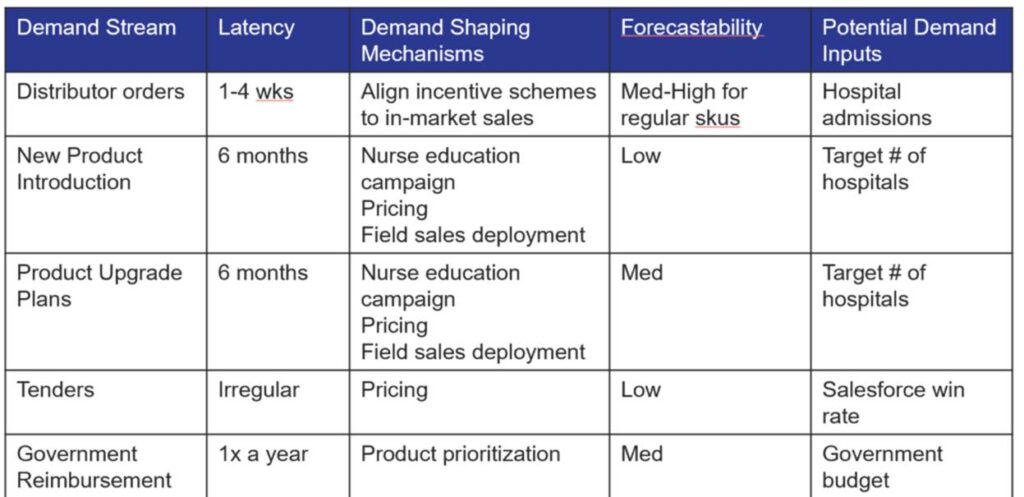

Here are examples from very different industries.

Example 1: Retail

Example 2: Food Ingredients

Example 3: Medical Device

After mapping the demand flows and identifying market data, latency, and forecastability, the class then designs bi-directional orchestration activities.

Conquering the Bullwhip and Driving Bi-Directional Orchestration

No one in the class had ever calculated the bullwhip effect. The range of bullwhip from the order to planned orders for manufacturing was 2.5-4.0. Outsourced manufacturing had a bullwhip of 8-9.

The combination of a negative Forecast Value Added (FVA) with a bullwhip in this range amplifies and distorts the signal to manufacturing, logistics and procurement increasing waste. In the class, we discuss how to reduce and manage the bullwhip and drive bi-directional orchestration channel (market) to supplier (market).

Some of the bi-directional orchestration strategies defined were:

“Use levers like postponement, alternate sourcing, product simplification, and alignment of shaping strategies to improve agility. Tactical and operational levers (e.g., alternate BOMs, route simplification) drive short-term responsiveness. Strategic levers (e.g., third-party manufacturing) build resilience.” The technologies often referred to as network design need to be re-depoloyed to help companies design and implement bi-directional orchestration strategies.

Better use data from hedging strategies: Manage risk from potential price drops/peaks before the cocoa is even harvested and to ensure price stability for product manufacturing. This makes costs more predictable. At the same time (inverted) futures markets drive contract prices near term and this drives decisions to

slow down or to speed up. Planning should understand and use better. Few align hedging strategies to bill of material logic.

Wrap-up

At the end of the class, the students are excited. They want to move forward. They ask, “How do I buy and align technology with what I have learned in the class?” I then sadly explain that there is no “off-the-shelf” technology available, and that most technologists/consultants do not understand the concepts. As a result, they must build it themselves with the help of their data scientists.

Making the shift is important for manufacturers. (General Mills is an example.) The one-size-fits-all, tight integration of APS to ERP degrades the forecast and accelerates the bullwhip effect. Most companies overlook the opportunity because they fail to measure it. The waste generated by our existing systems is enormous.

What now? My goal is to establish a guiding coalition that drives new thinking. My goal is to write case studies and quietly lead the revolution for change. Existing supply chain planing definitions are inadequate. The implosion in the General Mills case study for me, is symbolic for me on why I continue to do this research.

If you want to know more, I launched the large language model (LLM)–Ask Lora–that was used in the outside-in training to help guide the level of understanding in the classes. It is now available in an ask and answer format comercially. Business leaders can access a decade of my research on supply chain processes along with the financial benchmarking data from the Supply Chains to Admire work in the LLM.

In the use of “Ask Lora”, the organization sets the pace of training, and access is provided in the employee’s native language. The expert LLM also features videos of the class materials used in the six-module training, helping companies think differently through the deployment of outside-in planning. Give it a try and let me know your thoughts. I am convinced that we need to redesign planning to be outside-in.